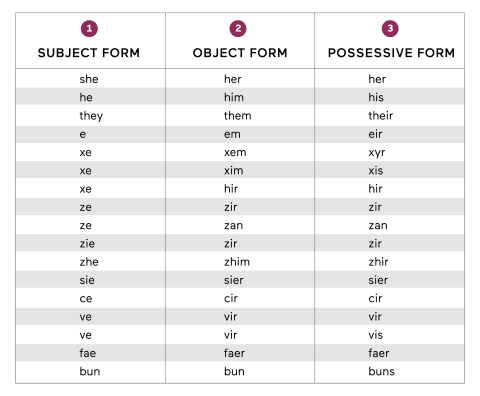

According to Dainis Graveris, a sex educator and founder of Sexual Alpha, neopronouns are a category of new pronouns that intentionally go beyond the traditional gender binary of masculine and feminine. While some people consider they/them/theirs pronouns as the go-to gender-neutral pronouns, they still limit individuals to three pronoun categories—he, she, or they. That’s where neopronouns come in. “Neopronouns empower folks who feel different from the rest of the world to be true to themselves when all other pronouns and labels don’t fit them,” Graveris explains to mbg. “For some people, these pronouns recognize both their masculine and feminine sides. For others, they help them express their unique gender identity to others.” That said, using neopronouns is still relatively uncommon in the United States. A 2020 Trevor Project study of 40,000 young members of the LGBTQ+ community found that while a full quarter of them use nonbinary pronouns of some sort, just 4% specifically used neopronouns. “These pronouns contain preexisting words that are used as pronouns. They are a unique way of exploring one’s understanding of their own gender,” Graveris explains. “For example, they can refer to fantasy/animé characters like fae/faer/faeself and vamp/vampself; animals like bee/beeself, kitty/kittyself, and bun/bunself; or other objects like star/starself and moon/moonself. Some people even use emoji-self pronouns.” Using neopronouns in full sentences is as simple as replacing the typical pronouns (he, she, him, her, etc.) with the neopronoun of the person you’re speaking about. To help, Heather Bonikowski, a lexicographer at Dictionary.com, suggests using the chart below. It shows traditional pronouns and some (not all) nonbinary pronouns, along with the grammatical function of each one to show how they’re used. “Many pronouns have a lot of cultural assumptions attached to them, but since neopronouns have no inherent link to gender, they can disrupt assumptions someone is making about someone’s gender,” they explain. This sentiment is echoed by the musician Dua Saleh, who uses the pronouns xe/xyr/xim, in a series of tweets shared on Twitter. “More recent neopronouns (new pronouns) have context within online subgroups created by trans/queer youth, creating shifts in ways [people] subvert Western heteropatriarchy and binaries,” xe tweeted. “It’s also really affirming to find the pronouns that are right for you even if they’re private to you. This is a privilege for me [because] often universally used languages are rooted in the binary.” Other neopronoun users say the decision to use them is rooted in fun and personalization. “Neopronouns are fun!” one user wrote in a recent Reddit thread. “They often fit better with how I feel, and they’re what you make of them! Are [they] masculine? Are they feminine? Are they gender neutral? I don’t care! It’s up to me.” While most of those neopronouns fell out of use or have not been in continuous use—like “hesher” and “ze”—Bonikowski notes that people have been trying to tinker with pronouns to reflect gender neutrality for centuries. “From the mid-1600s, English language style guides also promoted the use of ‘generic he’ to include any single person in the third person of any gender,” she explains. “During the 1970s and ’80s, perhaps related to second-wave feminism, ‘generic she’ was used by some writers. Some people alternated between using ‘she’ and using ‘he,’ or consistently wrote out the longer phrase ‘he or she.’ Novel forms like ’s/he’ were used in the 1990s and early 2000s.” Throughout history, neopronouns were even coined and pushed by state legislatures to clarify that laws should apply to any individual (whereas “generic he” can be read as applying only to men), she continues. Some newspapers and universities have also promoted the use of neopronouns: As described in linguist Dennis Baron’s book What’s Your Pronoun?: Beyond He and She, the Sacramento Bee used “hir” for almost 30 years starting in the 1920s, and Mississippi even entertained a bill proposed in 1922 to adopt the pronouns “hesh/hiser/himer” that failed by only one vote. More recently, the singular “they” has enjoyed a broader acceptance, even in edited, published writing. It’s used by many nonbinary people, though it does still have other uses for an unspecified singular referent. Neopronouns, however, are now primarily used by nonbinary people. And things have significantly improved when it comes to neopronoun inclusion, too: The Oxford English Dictionary added the neopronouns “ze” and “thon” in 2018 and “hir” and “zir” in 2019. In 2021, AI writing assistant Grammarly added support for neopronouns including xe/xem, ze/zir, ve/ver, and ney/nem. And social media sites like Facebook and Instagram allow users to pick from over 50 gender identities. Still, we have ways to go. According to Ley Cray, Ph.D., director of LGBTQIA+ Programming at virtual mental health clinic Charlie Health, the use of neopronouns in particular—especially noun-self pronouns—is a point of some debate even within TGNC (transgender and gender nonconforming) communities. “Some criticize the practice of using neopronouns on the grounds that, linguistically, they’re simply too challenging to use, making them unlikely to be taken up as a general part of the language,” Cray explains. “Others refer to some sort of mythical ‘purity’ of language and grammar—though these criticisms tend to rely on a misunderstanding of the historical development of language and also on the nature and role of grammar itself.” When it comes to TGNC communities, some defend the use of neopronouns and noun-self pronouns on the grounds that they expand the range of options for gender-nonconforming persons to relate to and express their gender. Others see the use of such pronouns as a sort of activism meant to reveal the absurdity of gendered language, to begin with. “At the same time, some within TGNC communities resist the widespread use of neopronouns and especially noun-self pronouns, with the idea being that such pronouns make it harder for the broader TGNC community to thrive,” Cray explains. “Such critics will suggest that neopronouns and non-self pronouns make it harder for TGNC persons who use more conventional pronouns to stand up against their own misgendering and also lead to an overemphasis on pronouns in the fight for TGNC rights, at the expense of focus on protecting accessible health care, protections in housing and employment, etc.” “This is largely where neopronouns come from—they are a way to get beyond binary pronouns and hence categories—pronouns are shorthand for those, so I would say it’s generally not just the pronoun but also what it represents and whether that representation fits,” she adds. Additionally, Kahn says people make sometimes accurate and sometimes inaccurate assumptions about someone’s gender based on their appearance, name, and pronouns. “What this says, though, is that people have to look, sound, present, and be named in specific ways to be seen as who they are. Using someone’s correct pronouns is one of the many ways we can respect someone and demonstrate that we see them as who they are.” Extended apologies or exaggerated corrections can be very uncomfortable for the person you’re referring to and can often put them in the position of having to expend emotional energy on consoling someone who just misgendered them. Queen adds that if we make a mistake and gracefully own it, it feels very different from being dramatic about how hard it is to remember someone’s pronouns. Don’t do the latter—it’s not about you.